Political branding, though often considered a modern phenomenon, has deep historical ties. In ancient Rome, emperors such as Augustus and Hadrian embarked on architectural adventures to not only display their power but also shape their public image and project their political visions. Similar to how today’s political candidates strategically cultivate their political brand through campaigning efforts, ancient Roman emperors employed physical structures as lasting symbols of their authority and vision.

With the upcoming 2024 U.S. presidential election, we can draw historical parallels between Augustus’ use of the Campus Martius and Hadrian’s redesign of the Pantheon to how modern politicians “dress” their campaigns.

One popular campaign branding strategy is introducing the political agenda’s physicality by creating a recognizable visual identity that effectively frames the politician’s narrative. By positioning their respective vision and values from a certain angle, politicians strive to cultivate and sustain brand loyalty.

Take, for instance, the political campaigns of Roman Emperors Augustus and Hadrian. Through an architectural medium, they sought to demonstrate the vitality of their empire while concurrently redressing their political brands to fit their respective political vision.

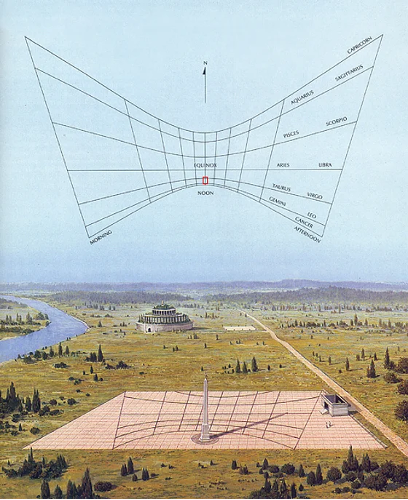

The three monuments of Augustus’ Campus Martius include the Mausoleum of Augustus, the Horologium-solarium Augusti, and the Ara Pacis Augustae. It was a public garden commissioned by Augustus to demonstrate that not only was he a “man” for the people (i.e. pontifex Maximus) but also a ruler who wanted to restore the Golden Age back to Rome. In the center of the Horologium-solarium was the Montecitorio Obelisk, which was originally made by Psamtik II in the sanctuary of the sun god Ra, who united Upper and Lower Egypt. Thus, carved on the two sides of the Obelisk base is a reference to how Egypt was reduced to the sovereignty of the Roman people who gave this gift to the sun. During Augustus’ time, there was a heightened interest in mathematical astronomy and astrology; there was also a growing tendency in literature and art to conceive time and to create a visual representation of the cosmos; the general Greco-Roman and Etruscan belief in cyclical time also contributed to the creation of this device by Augustus. Thus, the Horologium itself was a monarchic statement of Cosmic Imperium; while sundials existed before, the scale and elaboration (and thus, the programmatic relationship among these three monuments) were unique.

The size of this sundial reverses a typical relationship between the viewer and the sundial, where the viewer is compared to a subject of a powerful state. Since the sundial tells time at an imperceptibly slow speed, neither the size nor the speed is geared to human understanding. While the technology of the sundial itself was not new, Augustus’ exploitation of it was as it was not meant to be a practical time machine but rather a political device used to convey cosmic order. As a machine that ties the sun to time, the monument itself is perhaps a symbol of Augustus bringing back the Golden Age, or restoration of cosmic order, and thus the republic. The obelisk had a variety of functions: a victory monument over Egypt, Cleopatra, and Marc Anthony (Battle of Actium in 31 BC); a political statement of immense power and world rule; and a religious object that honors the sun god. Thus, Augustus shows a claim to divinity by bringing in a new Golden Age;. However, he is careful not to be explicit by comparing himself to a god, he views himself to be god-adjacent (i.e, divine-like) or a ruler approved by the gods.

In the Ara Pacis Augustae, Augustus employs notions of the abstract, ideal, and perpetual sacrifice; the personifications of his provinces suggest that the altar is a metaphor for Rome’s world domination. In fact, the personifications of the provinces supported the altar in such a way that their acquisition would elevate the Roman Empire to new heights. The presence of ten lictors is also a clear sign of imperium maius. The Lion-griffin terminals crowning the upper corners of the inner altar are significant to his political message since griffins are traditionally depicted to be protecting age; in this manner, the griffins are guarding the gold of the Pax Augusta, that is, the Golden Age in Rome’s history. Moreover, on September 24th, the shadow is pointed through the western door of the altar into the altar as if the sun itself was pointing to the altar. In this Campus Martius, Augustus promotes the notion that although he is a man of the people (publicizing the gardens), he also illustrates that he is restoring the Golden Age to Rome with the approval of the sun god(s).

In my own opinion, this could perhaps be an early Roman predecessor to political astroturfing. Hadrian, in contrast, ruled Rome in a period that ushered in a new “Pax Romana.” Instead of expansion of the empire, he was known to consolidate various cultures. Considered a cosmopolitan by vision and politics, Hadrian spent little time in Rome but more time experiencing and taking in other cultures. This was evident in his villa, which reflected his exposure to a vast range of ideas from his travels across the empire (i.e., the empire was not a grid-like structure of order). While his private villa had independent buildings and elements from different cultures, it was still accessible and pleasing; this shows that while he was unifying the Roman Empire, he did not want to nor intend to create a single race.

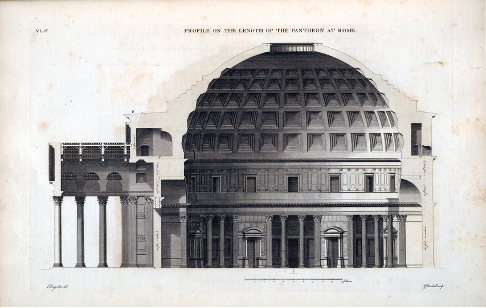

The redesign of the Pantheon was considered to be Hadrian’s most significant architectural contribution in 126 CE. Agrippa built the original Pantheon, which faced South and was entirely rectangular. In Hadrian’s redesign, the new porch was built over the remains of the original pantheon; the entrance displays Agrippa’s name; and a significant difference is that the new porch would face due North and line up with the cardinal directions. Hadrian also added the rotunda, which is significant because the spherical geometry represents the symbol of infinite perfection. The oculus is a significant component because the only source of light was light “from the heavens.” This pantheon, in which the temple was devoted to all the gods, captured the new times under Hadrian. When you first approach the Pantheon, you see Agrippa’s name, which is an homage to the old Rome. Then, the rectangular courtyard is a familiar pathway, a representative of a transition from the old to the new Rome; once you enter the Rotunda, you face the new reality of the new Roman Empire, which is a vast and all-encompassing sphere. Perhaps the shift from the South to the North direction also supports the shift from old Rome to a new reality of Rome. While Augustus’ Campus Martius was to endorse a political message to return Rome to a Golden Age, Hadrian’s redesign of the Pantheon reflected his vision to take Rome in a new direction.

Hadrian’s cosmopolitan approach—through his redesign of the Pantheon—symbolized unity, cultural consolidation, and a new Rome, which can be contrasted with Augustus’ emphasis on Rome’s supremacy and desire to return to its Golden Age.

By comparing the three monuments of the Campus Martius commissioned by Augustus with Hadrian’s redesign of the Pantheon, we can see the historical applications of modern concepts on political branding and rebranding. While fewer architectural endeavors are being undertaken in our modern political climate, political leaders throughout history consistently and infamously use marketing strategies to fuel their campaign base. For instance, Kamala Harris is frequently captured donning Converse sneakers as a symbol of relatability and approachability, adding a “for the people” element to an otherwise professional image; the cosmopolitan approach is not dissimilar from Hadrian’s political intentions. Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan famously captures his vision of returning America to a “Golden Age,” which, to a great degree, parallels Augustus’ ideals for Rome. The concept of “branding”—from historical projects of redesigning pantheons to modern production of recognizable merchandise—is a timeless political tool. Ultimately, these emperors’ new ‘clothes’ manifest in brand loyalty, employing visual structures to reflect and project their political values and vision.

With this upcoming election, it will be fascinating to be on the lookout for how Donald Trump and Kamala Harris “dress” their political campaigns. I’ll give you the first hint! The red “Make America Great Again” hat is commonly associated with which candidate?

Author’s note: Information regarding the analysis of Augustus’ Campus Martius and Hadrian’s Pantheon can be cited to Dr. Han Tran from the University of Miami Department of Classics. This blog piece was in part inspired by my formal education in Dr. Tran’s ‘Ancient Greek and Roman Art’ course at the University of Miami.